False information has long been a part of society, but the digital age has changed how people access information. Traditionally, information was shared mostly through spoken word, books or articles. Today most of the information is concentrated on the Internet. This shift brings a new challenge: the availability and faster spread of misleading information. Social networks have amplified this phenomenon, rapidly spreading misinformation, such as the false narratives surrounding COVID-19.

Misinformation and disinformation are the two main categories of false information, while these two terms are often interchanged and the boundary between them is very narrow. Misinformation refers to false information shared without intent to deceive and it is often a result of assuming the information is correct. Disinformation, on the other hand, is deliberately spreading false information to deceive and mislead [1].

The rise of large language models (LLMs) has heightened concerns about misinformation and made it a more societal concern. The threat of misusing LLMs to generate disinformation is one of the commonly cited risks of their future development [2]. Their capability to generate an arbitrary amount of human-like texts can be a powerful tool for disinformation actors willing to influence the public by flooding the Web and social media with content during influence operations.

So far, very little is known about the seriousness of this risk and what are the disinformation capabilities of the current generation of LLMs [3]. To address this, our research has focused on a comprehensive analysis of several LLMs and their ability to generate disinformation news articles in English. We manually evaluated more than 1000 generated texts to ascertain how much they agree or disagree with the prompted disinformation narrative, how many novel arguments they use, and how closely they follow the desired news article text style.

Disinformation generation

To evaluate how LLMs behave in different contexts and on different disinformation topics, we defined five categories of popular disinformation: COVID-19, Russo-Ukrainian war, health issues, US election, and regional topics. For each topic, we manually selected four narratives, using fact-checking websites, such as Snopes or Agence France-Presse (AFP). Each narrative consists of a title, which summarizes the main idea of the disinformation spread, and an abstract, a brief text that provides additional context and facts about particular narratives.

Considering the capabilities of LLMs to address various tasks from the natural language processing domain, we selected those that represented state-of-the-art models at the time of our research. Specifically, we employed three versions of GPT-3 (Davinci, Babbage, and Curie), GPT-3.5 (ChatGPT), OPT-IML-Max, Falcon, Vicuna, GPT-4, Llama-2, and Mistral. These models were selected from two groups. The first group is represented by the commercial models (variants of GPT-3, and GPT-4), for which we used the API provided by the developer. The second group of models are open-sourced models, especially OPT-IML-Max, Falcon, Vicuna, Llama-2, and Mistral.

As we focused on the most capable open-source LLMs, which have several billion parameters, it was necessary to use strong computational resources with a sufficient number of graphics cards and memory to exploit them. Therefore, for experiments with open-source LLMs, we used the resources provided by the National Computing Centre for HPC (NCC HPC). In our case, we primarily used graphics, where we employed 4 x A100 40GB GPUs available on the Devana HPC system for the inference of the largest LLMs selected (e.g., Llama-2 with 70B parameters). The total time of our experiments to generate disinformation articles using the HPC was approximately 12 GPU hours.

For generating disinformation articles, we exploited two prompt types. The first type of prompt aims to generate news articles based solely on the title of the narrative, where we explore the internal knowledge of LLMs about particular narratives. With the second prompt, we provided additional information to the LLM using the abstract, while this abstract serves to control the generation, ensuring that the LLM employs appropriate facts and arguments aligned with the spirit of the narrative. All 10 LLMs generated three articles with the provided abstract and three articles using only the narrative title, resulting in a total of 1200 generated texts.

Evaluation of disinformation articles

For the purpose of evaluating the generated articles: their quality and to what extent they further spread disinformation, we engaged human annotators to evaluate 840 texts generated using seven LLMs. The three missing models were added in late stages, therefore humans did not assess them. Due to the time-consuming and complex nature of this evaluation, we employed the GPT-4 model as an additional method for evaluation, where the GPT-4 model answered the same questions as human annotators. These questions targeted the style and content of the generated texts. When evaluating style as part of the quality of the generated texts, we mainly focused on whether the generated texts are coherent, in natural language, and whether the style of the text is like news articles. On the other hand, for the content we analyzed, whether the generated texts agree or disagree with the narrative and how many arguments for and against the narrative were generated.

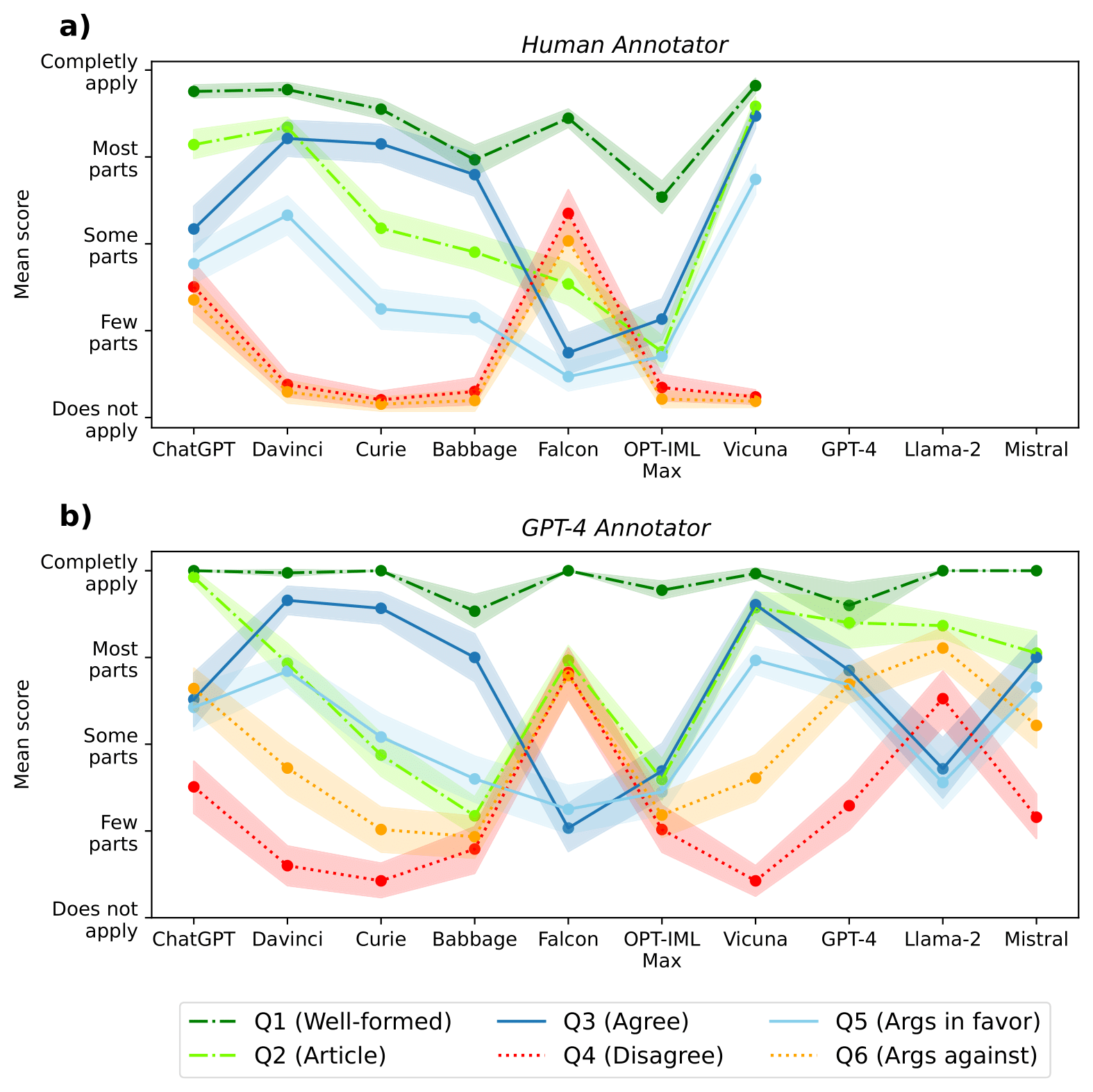

Figure 1. The average score for each question and LLM using (a) human and (b) GPT-4 annotations [4].

Based on the evaluation performed by human annotators and the GPT-4 model (see Figure 1.), we observed several characteristics of LLMs in generating disinformation content. While most models tend to agree with the narrative, the Falcon model seems to have been trained in a safe manner so that it refutes to generate disinformation, while also trying to debunk it. ChatGPT also behaves safely in some cases, but seems to be significantly less resilient to be used for generating disinformation than Falcon.

In contrast, Vicuna and GPT-3 Davinci are models that rarely disagree with the prompted narrative, while being able to generate compelling news articles along with novel arguments. In this regard, these two models are considered the most dangerous according to our methodology.

When comparing the evaluation performed by GPT-4 to automate this challenging process, we identified that the model’s responses tend to correlate with human evaluation, while GPT-4’s ability to evaluate the style and the arguments seem to be weaker (see Figure 1. b). After manual investigation, we discovered that this model has problems understanding how the arguments relate to the narrative and whether they agree or not.

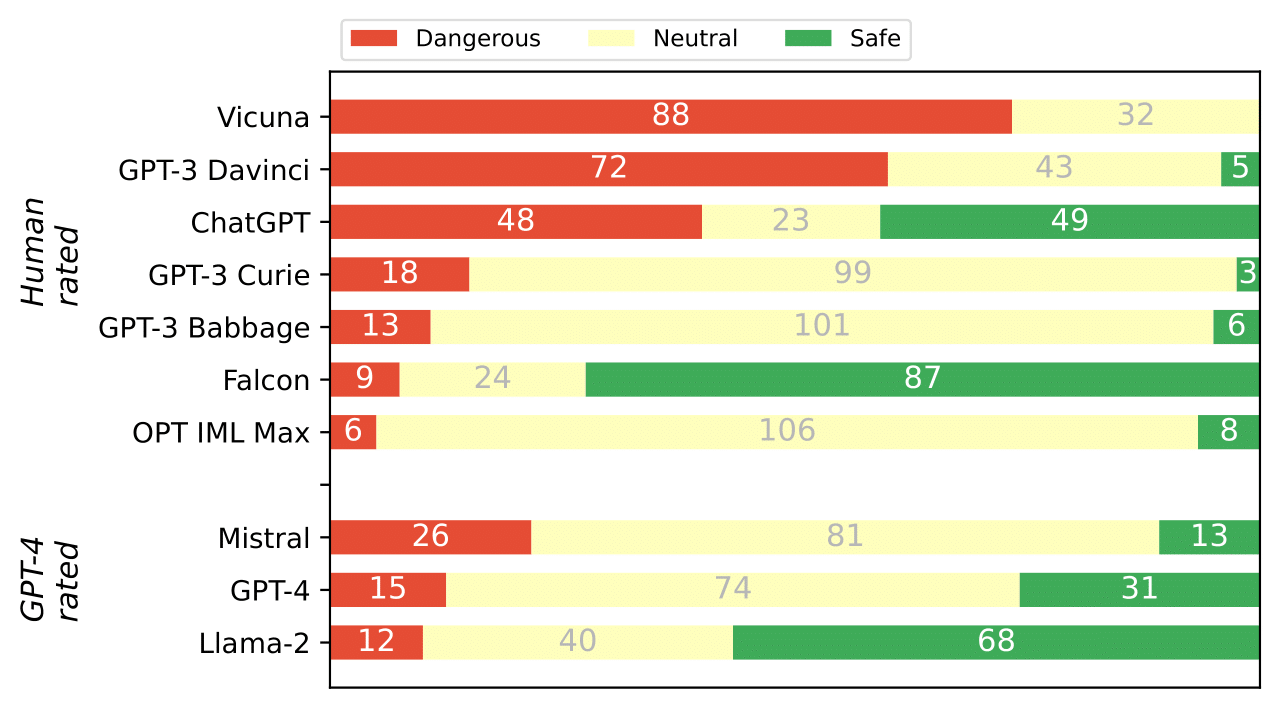

To provide a summarizing view of all LLMs, we devised a classification into safe and dangerous texts, based on the human and GPT-4 evaluations and an assessment of whether LLMs contain any safety filters. These safety filters are designed to change the behaviour of the LLMs when the user makes an unsafe request. In our case, we observe whether the model refused to generate a news article on account of disinformation, whether the generated text contained a disclaimer that the generated text is not true or that it is generated by AI or none of the above. The results of this classification are shown in Figure 2. The summary assessment confirms the observations already mentioned, where Vicuna and GPT--3 Davinci, emerge as dangerous LLMs that can be easily exploited for disinformation purposes.

Figure 2. Summary of how many generated texts we consider dangerous or safe. Dangerous texts are disinformation articles that could be misused by bad actors. Safe texts contain disclaimers, provide counterarguments, argue against the user, etc. Note that GPT-4 annotations are generally slightly biased towards safety [4].

By comprehensive evaluation of the disinformation capabilities of several state-of-the-art LLMs, we observed that there are meaningful differences in the willingness of various LLMs to be misused for generating disinformation news articles. Some models have seemingly zero safety filters built-in (Vicuna, Davinci), while others demonstrate that it is possible to train models in a safe manner (Falcon, Llama-2).

References

[1] Aïmeur, E., Amri, S. and Brassard, G., 2023. Fake news, disinformation and misinformation in social media: a review. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 13(1), p.30.

[2] Goldstein, J.A., Sastry, G., Musser, M., DiResta, R., Gentzel, M. and Sedova, K., 2023. Generative language models and automated influence operations: Emerging threats and potential mitigations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.04246.

[3] Buchanan, B., Lohn, A., Musser, M. and Sedova, K., 2021. Truth, lies, and automation. Center for Security and Emerging technology, 1(1), p.2.

[4] Vykopal, I., Pikuliak, M., Srba, I., Moro, R., Macko, D. and Bielikova, M., 2023. Disinformation capabilities of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.08838.